courtyard is an exhibition space.

A place of gathering and experimentation, defined by the projects, contributions and events it hosts at a given moment, and driven by the associations that emerge from these. Visitors are invited to wander across the open space.

Hemlock Forest by Μoyra Davey

31 Mar 2022

Moyra Davey, Hemlock Forest, HD video with sound, still, 41 min 15 sec, 2016

Co-commissioned and co-produced by Bergen Kunsthall & la Biennale de Montréal. Courtesy the artist & greengrassi, London

Hemlock Forest was presented at courtyard, Thursday 31 March–Sunday 3 April 2022, 7pm (CET)

Haris Epaminonda, Lyrical apparitions that commune with the past by Dominic Eichler

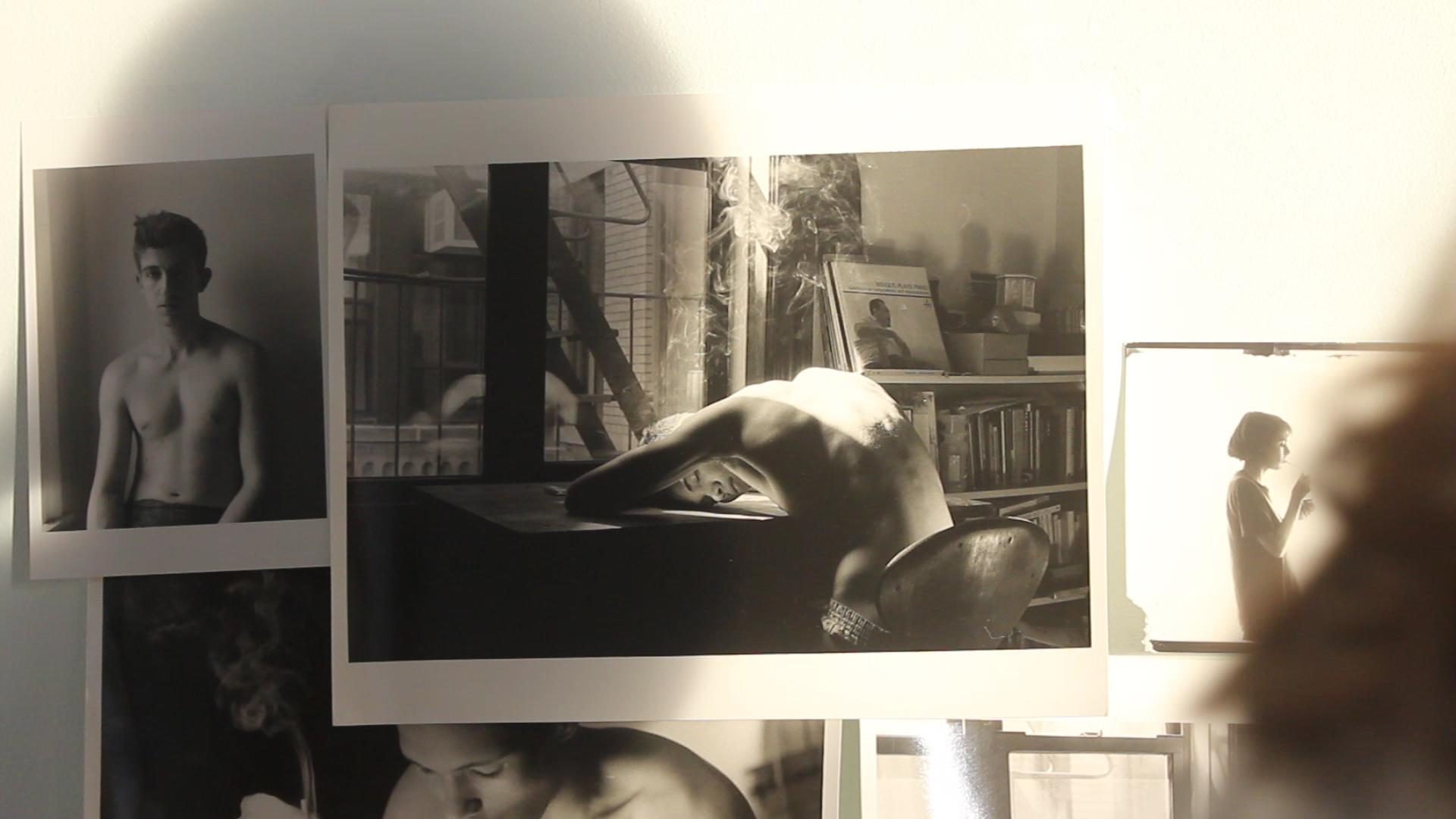

Haris Epaminonda, Tarahi V, still, video PAL 4:3, video, sound, 3.10 min, 2007

The ghostly folds of a curtain, a couple strolling backwards on a sun-dappled path, the limpid eyes of a disconsolate diva: these are just some of the suspended moments captured in the video works of Haris Epaminonda. In the last few years, the artist has produced a series of radiant, emotional, audio-visual vignettes, which are long enough to soak into the viewer’s consciousness yet short enough to assume the qualities of a vision: they come and go fleetingly, but linger in the head like an afterimage. Reality is kept at arm’s length, its absence not particularly noticed, while the present is lost in a fictionalized past.

Most of Epaminonda’s recent video works are based on re-shot excerpts of film and television footage – principally the Greek soap operas and kitsch romantic films from the 1960s that used to fill up Sunday afternoons in the artist’s Cypriot childhood – which she then subtly reworks. Sometimes local celebrities appear in her films, but, in contrast to the early works of Francesco Vezzoli or T.J. Wilcox, they don’t do so in order to emphasize a phantasmal communion with their constructed identities. The scenes that she chooses to work with are not instantly recognizable from the original narrative, so the culled images are effectively stripped of their initial meaning and context. These out-takes are then edited and adapted in a variety of ways: the film’s speed and direction are changed, sections are distorted, its colour is intensified, or a poignant soundtrack, such as a piano composition by Alexander Scriabin, is added. Most significantly, she also superimposes footage to make surreal composites: an indoor scene, say, might also have traces of fireworks glimmering through it. While these are all common manipulation techniques of digital video, Epaminonda uses them with captivating sensibility. In Tarahi V (Turmoil V, 2007), for example, in a scene that recalls elements of the work of both René Magritte and Alfred Hitchcock, we see the back of a well-dressed, motionless couple staring out into a blue sky where a pair of coffee cup-ring shaped clouds appear.

Recently, in the attic space of Rodeo – a new gallery housed in a restored tobacco warehouse in Istanbul, in the sort of inner-city neighbourhood that might have inspired Pier Paolo Pasolini – Epaminonda beamed onto a wall the apparition-like video Tarahi II (Turmoil II, 2006). The work consists of footage shot from a hotel-room television by the artist when she was in Egypt. It shows a regal, middle-aged woman with an ebony bouffant in a series of close-ups in which she turns to look at the camera with incredible pathos, her glittering eyes seemingly having subsumed the bitter tears of a thousand disappointments. Epaminonda has compiled all the scenes in which the unnamed actor appears alone, effectively putting the character in conversation with herself. Partway through the film, which is underscored by a lyrical piano soundtrack, something odd and unexpected happens. Twin boys, with long noses, big ears and hair carefully parted to one side, make a sudden appearance. Standing side by side, they look at each other and then at the camera as if to say: what on earth is this woman going on about? It’s a highly effective break – one that stops the work from wallowing, and that deals the viewer yet another serving of displaced emotion.

There is a particular flow, and a certain colour and light, to be found in nearly all of Epaminonda’s works. Her videos look lush and delicious, like highly saturated Technicolor films exuding the vivid hues of melodrama favoured by Douglas Sirk: pulsing red, oceanic-sky blue, yellows, browns and greens facilitating between the tonal factions. Light and movement, however delicate, are treated as adequate subjects. Epaminonda’s work first came to the attention of a wider audience at this year’s Venice Biennale with her installation in the Cyprus Pavilion. (This two-person exhibition with Mustafa Hulusi, curated by Denise Robinson, was notable for being the first time the Greek-Cypriot funding body had allowed a Turkish-Cypriot artist to participate.) Epaminonda combined a room of videos with works from an ongoing series of untitled black and white collages, assembled using cuttings from her collection of found photography books about countries and cities. For the artist, the processes of editing videos and composing collages are fundamentally related, in that both entail making decisive cuts. Her collages distinguish themselves from the reams of others that have been produced by emerging artists in recent years. Take Untitled *13 (2005–6), for instance, in which a child in a cradle is claustrophobically loomed over by multiple, well-meaning families; or those depicting Gothic cathedrals whose windows, walls or towers have become mirrors of altered skies. Typically these collages work through cut-aways, layers or visual revelation rather than a juxtaposition or synthesis of disparate images. Epaminonda told me that she is not nostalgic for the pasts she mines, but rather her work attempts to merge different realities – mediated yesteryear, everyday life and the future – onto

a single plane.

Frieze

Issue 111

1 November 2007