On Using “I” and First-person Narration by Iman Issa with Moyra Davey

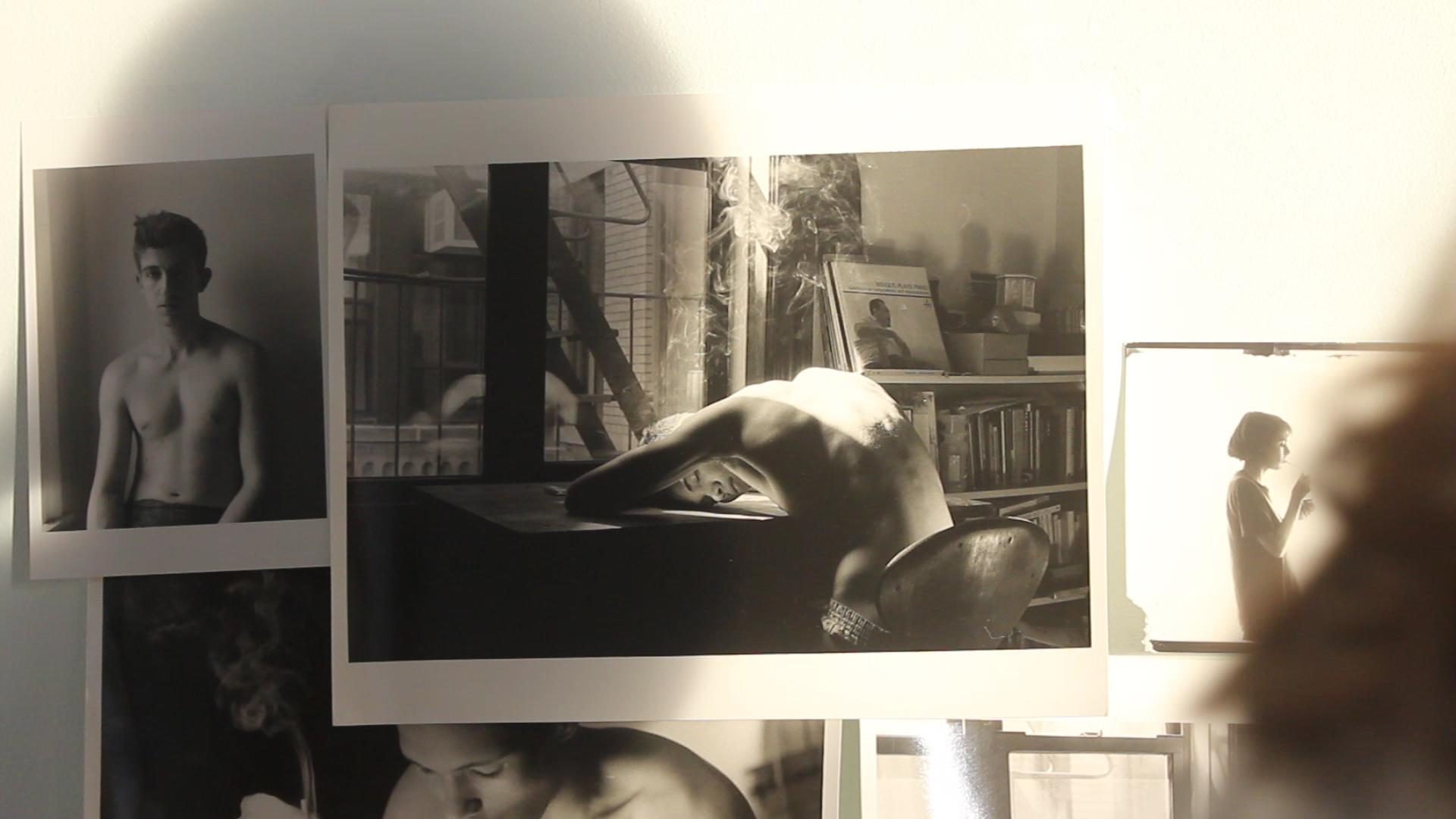

For several years now I’ve been engaged in an itinerant conversation with Moyra Davey. It began when I wrote a short paragraph on her film Les Goddesses for Artforum concerning her use of first person narration. At the time, I was thinking a great deal about what it means to use oneself as the source of one’ s work—trying to make sense of the “I” through which we choose to speak and articulate positions, sentiments, and facts. Moyra’ s film appeared to pierce through these issues head on and became a new lens through which to view the rest of her work. Her photographs, videos, and writings completed over three decades started to form a coherent whole in my mind, and I was eager to revisit her work from my newly found angle. Until now, I’d never had the chance to properly unpack these ideas. This conversation is an attempt at doing that.

*

Iman Issa: One of the key moments that brought me further into your work was seeing Les Goddesses in 2011, both at the Whitney Biennial and during your solo exhibition at Murray Guy. At that time, I was struggling with the use of what one might describe as the “personal voice”. I felt uncomfortable with the enormous leeway an artist can have when using such a voice. As if it gave one license to draw connections between different elements and narratives with no justification beyond the incontestable claim of subjective inclinations. At that same time, I was convinced that certain elements and topics could only be accessed with it. Seeing your work was revelatory; I felt it was using the personal voice differently. How would you describe your relationship to that voice?

Moyra Davey: Fundamentally I’m interested in storytelling, although I don’t often put it like that. Some background on Les Goddesses: I had just moved to Paris for ten months and was flooded with memories of when I lived there at the age of eighteen, and had hugely struggled with the city and the people I knew at the time. I wanted to write about what I considered “unspeakable” memories. That was the idea, the “agenda”, even though a big part of me thought it was impossible. A well-known writer, whose name escapes me, counseled that I should write from a place of the greatest discomfort. Knausgaard is able to do it via auto-fiction.

For myself, I can only imagine that via fiction—a novel, a story—genres I have never tried. Les Goddesses was an attempt to get close to painful material, and I came up with this device of linking my story to these historical, literary women: Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley. This was something of an enabler; a way to create parallelism and give the ‘muck’ a foil.

But Borges points out that people “long for confessions”, and viewers have told me the same, that they prefer the grittier, autobiographical material in my narratives. Les Goddesses became somewhat of an idealized portrait of my family. And so in this new video that I’ve just begun to edit, tentatively titled Hemlock Forest, I’m asking what it would mean to revisit Les Goddesses, but to show us (my sisters and myself) as we are now, not via photos taken thirty-five years ago when we were in our heyday. I cite what you wrote in Artforum, about Les Goddesses having a “desperate” quality. I thought you hit the nail on the head.

Read More